I am trying to update the image links today but it is not easy…I have to prepare for my talks Fri and Sat this week. so after that I will try to update the image links.. today I discovered that the extension.org website image links all gone bad….

1. Head

Head of the honey bee Head of the honey bee | The head is the center of information gathering. It is here that the visual, gustatory and olfactory inputs are received and processed. Of course, food is also input from here.Important organs on or inside the head: 1. Antennae, 2. Eyes, 3. Mouth parts, 4. Internal structures. |

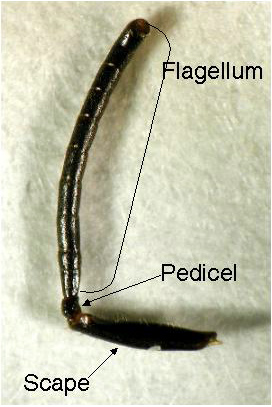

1.1 Antenna(e)

Because honey bees live inside tree cavities (natural) or hives (man-made), both of which have little light away from the entrance. Smell and touch therefore are much important for them than visual when inside the nest.

The honey bee antennae (one on each side) house thousands of sensory organs, some are specialized for touch (mechanoreceptors), some for smell (odor receptors), and others for taste (gustatory receptors). It used to be thought that honey bees couldn’t hear any airborne sound because they do not have pressure-sensitive hearing organs (like our ear-drums or similar structures on the legs of katydids). Because of this, scientists were puzzled the ways through workers can perceive the buzzing sound produced by workers during waggle dances. Around 2011, it was discovered that bees can indeed ‘hear’ airborne sound in close range, this is through sensing the movement of air particles by the hairlike mechanoreceptors on the antennae. This discovery helped the construction of robot bees that can be directed to dance (by a computer) inside a hive and guide workers to a specific location.

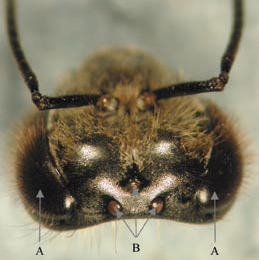

1.2 Eyes

Honeybee eyes. A – Two compound eyes. B – Three simple eyes. From “Beekeeping in Tennessee” Honeybee eyes. A – Two compound eyes. B – Three simple eyes. From “Beekeeping in Tennessee” | |

| Honey bees have two compound eyes that make a large part of the head surface. Each compound eye is composed of individual cells (ommatidium, plural ommatidia). Each ommatidium is composed of many cells, usually including light focusing elements (lens and cones), and light sensing cells (retinal cells). Workers have about 4,000-6,000 ommatidia but drones have more 7,000-8,600, presumably because drones need better visual ability during mating. Honey bees have a combined mouth parts than can both chew and suck (whereas grasshoppers can chew and moth can suck, but not both). This is accomplished by having both mandibles and a proboscis. As in most insects, bees eyes are not designed to see high resolution images like our eyes do, but rather they see a mosaic image but are better than us for motion detection. Bees also have three simple eyes that are called ocelli (singular: ocellus), near the top of their head. Ocelli are simple eyes that do not focus but provide information about light intensity. |

1.3 Mouthparts

(c) Zachary Huang. (c) Zachary Huang. | |

| Honey bees have a combined mouth parts than can both chew and suck (whereas grasshoppers can chew and moth can suck, but not both). This is accomplished by having both mandibles and a proboscis. The mandibles are the paired “teeth” that can be open and closed to chew wood, manipulate wax, cleaning other bees, and biting other workers or pests (mites). The proboscis is mainly used for sucking in liquids such as nectar, water and honey inside the hive, for exchanging food with other bees (trophallaxis), and also for removing water from nectar. The workers can put a droplet of nectar between the proboscis and the rest of the mouth parts to increase the surface area, and slowly moving the proboscis back and forth. |

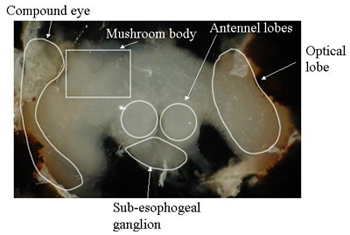

1.3 Internal organs

(c) Zachary Huang

(c) Zachary Huang

Honey bee mandibular gland. (c) Zachary Huang

The main internal organs in the head are the brain and subesophageal ganglion, the main component of the nervous system, in addition to the ventral nerve cord that runs all the way through the thorax to the abdomen. Yes, the bee does have a brain, a pretty sophisticated one too. The brain has a large area for receiving inputs from the two compound eyes, called optic lobes. The next largest input are from the antenna (antenna lobes). One important region in the middle of the brain is called the “mushroom body” because the cross section resembles two mushrooms. This area is known to be involved in olfactory learning and short term memory formation, and recently shown to be also important in long term memory formation in insects.

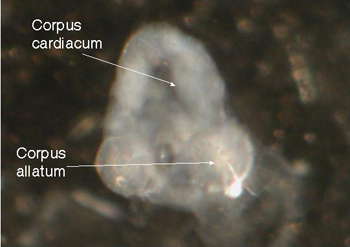

There are also endocrine organs attached to the nerve cords, very close to the esophagus (the food canal). One is called the corpora allata (CA, in Latin it means the body beside the food canal), which is the only source of one important hormone, juvenile hormone, which is involved in both the queen-worker differentiation, and also division of labor in workers. The other one is called corpora cardiaca (CC, the body near the heart), which is a neurohemal organ and stores and releases another hormone (PTTH, prothoracicotropic hormone). PTTH can stimulate the production of ecdysteroids, by a gland located in the thorax, the prothoracic gland.

Lastly there are exocrine glands inside the head also, most notably the mandibular glands, the hypopharyngeal glands and the salivary glands. Mandibular gland is a simple sac-like structure attached to each of the mandibles. In the queen this is the source of the powerful queen pheromone.

In young workers the gland produces a lipid-rich white substance that is mixed with the secretion of hypopharyngeal glands to make royal jelly or worker jelly and fed to the queen or other workers. In old workers (foragers) the gland also produces heptanone, a component of the alarm pheromone. Similarly hypopharyngeal glands produce protein-rich secretions when young (nurses), but produce invertase (an enzyme to break down sucrose into fructose and glucose) in foragers. The glands is consisted of a central duct (which is coiled between the front cuticle and the brain) with thousands of tiny grape-like spheres (acini, singular: acinus). The secretion flows to the mouth through the long duct. The glands are large in size (hypertrophied) in nurse bees but become generated in foragers. There is also a pair of head salivary glands inside the head. The glands produce saliva which is mixed with wax scales to change the physical property of wax.

Honey bee hypopharyngeal gland. (c) Zachary Huang Honey bee hypopharyngeal gland. (c) Zachary Huang |  Honey bee salivary gland. (c) Zachary Huang Honey bee salivary gland. (c) Zachary Huang |

2. Thorax

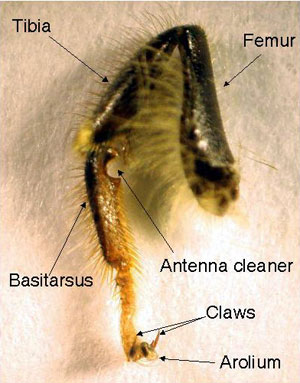

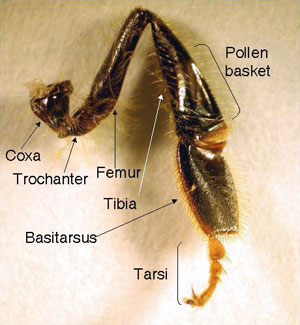

The thorax is the center for locomotion and has three segments, each with a pair of spiracles for letting in air. Bees have 2 pairs of wings and three pairs of legs. The legs are very versatile, with claws on the last tarsomere, allowing bees to have good grip on rough surfaces (tree trunks etc), but also with a soft pad (arolium) to allow bees to walk on smooth surfaces (leaves or even glass!). There are also special structures on legs to help bee get more pollen. The thorax is the center for locomotion and has three segments, each with a pair of spiracles for letting in air. Bees have 2 pairs of wings and three pairs of legs. The legs are very versatile, with claws on the last tarsomere, allowing bees to have good grip on rough surfaces (tree trunks etc), but also with a soft pad (arolium) to allow bees to walk on smooth surfaces (leaves or even glass!). There are also special structures on legs to help bee get more pollen. |

2.1 Legs

On the front leg, there is a special structure used for cleaning antenna (when too many pollen grains stuck there), properly called the “antenna cleaner”.

Front leg Front leg |  Hind leg Hind leg |

2.2 Pollen Basket

Pollen basket on hind leg Pollen basket on hind legAnother notable special structure on legs is called the pollen basket (corbicula), located on the tibia of the hind leg, which is used for carrying pollen or propolis for foragers. It is a concave surface with hairs on the edges and a central long bristle that goes through the pollen pellet or propolis so the load would stay while bees are flying. |

2.3 Wings

The front wings are larger than the hind wings and the two are synchronized in flight with a row of wing hooks (humuli, singular: humulus) on the hind wing that would hitch into a fold on the rear edge of the front wing.

One set of front and rear wings One set of front and rear wings |

Close-up of hooks that hold the wings together Close-up of hooks that hold the wings together |

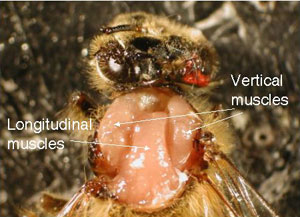

The flight muscles exposed

The flight muscles exposed

The wings are powered by two sets of muscles inside the thorax, the longitudinal and verticle muscles. During flight, when the longitudinal muscles contract, the thorax raises its height, so the wings are lowered because of fulcrum like structure (pleural plates) near the wing base. Conversely, when the vertical muscles contract, it shortens the height of thorax, raising the wings. The honey bee flight muscles can contract several times with one single nerve impulse, allowing it to at a faster rate.

3. Abdomen of the Honey Bee

On the surface the abdomen has no special outside structures, but is the center for digestion and reproduction (for drones and queens). It also houses the sting, a powerful defense against us humans. A worker, a drone, and a queen can be distinguished by the size and shape of their abdomen. The queen pictured here was laying eggs, as can be seen by her large abdomen.

A worker, a drone, and a queen can be distinguished by the size and shape of their abdomen. The queen pictured here was laying eggs, as can be seen by her large abdomen.

3.1 Wax Scales

Honey bees produce wax on their abdomens as scalesWorkers around 6-12 days old can produce wax scales in their four pairs of wax glands. The glands are concealed between the inter-segmental membranes, but the wax scales produced can be seen, usually even with naked eyes. The scales are thin and quite clear. After workers chew them up and add saliva, it becomes more whitish Honey bees produce wax on their abdomens as scalesWorkers around 6-12 days old can produce wax scales in their four pairs of wax glands. The glands are concealed between the inter-segmental membranes, but the wax scales produced can be seen, usually even with naked eyes. The scales are thin and quite clear. After workers chew them up and add saliva, it becomes more whitish |

3.2 Digestive tract

The digestive tract of the honey bee The digestive tract of the honey bee Tracheal system (silver-looking networks) on the midgut of a worker. The tracheal tubes branches smaller and smaller untill it goes into indivudual cells directly to deliver oxygen.The digestive tract is rather typical for an insect. The esophagus starts near the mouth, goes through an opening in the brain, through the thorax, and enlarge near the end to form the honey crop, which can expand to quite a large volume (nearly half of the abdomen in a successful forager). There is a special structure called preventriculus near the end of the crop. The proventriculus has sceleritized teeth-like structure, and also muscles and valves. These structures allow the workers to remove pollen grains in the nectar, and also stopping the backflow of food being digested into the crop, ensuring that the nectar is never contaminated. The contents of the crop can be spit back into cells, or feed to other workers, as is the case of nectar collected by foragers. The ventriculus (midgut) is the functional stomach of bees and is the largest part of the intestine. Malpighian tubules are small strands of tubes attached near the end of ventriculus and functions as the kidney, it removes the nitrigen waste (in the form of uric acid, not as urea as in humans) from the hemolymph and the uric acid forms crystals and is mixed with other solid wastes.The rectum is also quite expandable (just like the crop, and both are extoderma structures, and both are lined with a chitin layer, enabling workers to refrain of defecation for up tomonths (for example bees in Michigan here might have their last defecation flights in November, and then again in March the next year). Tracheal system (silver-looking networks) on the midgut of a worker. The tracheal tubes branches smaller and smaller untill it goes into indivudual cells directly to deliver oxygen.The digestive tract is rather typical for an insect. The esophagus starts near the mouth, goes through an opening in the brain, through the thorax, and enlarge near the end to form the honey crop, which can expand to quite a large volume (nearly half of the abdomen in a successful forager). There is a special structure called preventriculus near the end of the crop. The proventriculus has sceleritized teeth-like structure, and also muscles and valves. These structures allow the workers to remove pollen grains in the nectar, and also stopping the backflow of food being digested into the crop, ensuring that the nectar is never contaminated. The contents of the crop can be spit back into cells, or feed to other workers, as is the case of nectar collected by foragers. The ventriculus (midgut) is the functional stomach of bees and is the largest part of the intestine. Malpighian tubules are small strands of tubes attached near the end of ventriculus and functions as the kidney, it removes the nitrigen waste (in the form of uric acid, not as urea as in humans) from the hemolymph and the uric acid forms crystals and is mixed with other solid wastes.The rectum is also quite expandable (just like the crop, and both are extoderma structures, and both are lined with a chitin layer, enabling workers to refrain of defecation for up tomonths (for example bees in Michigan here might have their last defecation flights in November, and then again in March the next year). |

3.3 The sting

The exuded sting with a small drop of venom on it. The exuded sting with a small drop of venom on it. | |

A worker bee trying to get away after stinging. The sting has barbs preventing the sting to be pulled out, part of her digestive system is seen dragging behind her. Once a worker bee stings, the bee tries to get away. The sting has barbs preventing the sting to be pulled out. The sting apparatus breaks off and is left behind. The sting, venom gland, and muscles controlling the gland, will work autonomously to pump venom into the victim. Alarm pheromone is also released to “mark” the victim. This sends a signal to other bees to sting you again. A worker bee trying to get away after stinging. The sting has barbs preventing the sting to be pulled out, part of her digestive system is seen dragging behind her. Once a worker bee stings, the bee tries to get away. The sting has barbs preventing the sting to be pulled out. The sting apparatus breaks off and is left behind. The sting, venom gland, and muscles controlling the gland, will work autonomously to pump venom into the victim. Alarm pheromone is also released to “mark” the victim. This sends a signal to other bees to sting you again. |

3.4 Reproductive system

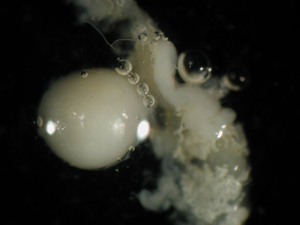

Ovary of a laying queen. Individial ovarioles can be seen, with more mature eggs shown as yellowish. Egg cells move down the tube of overioles and become larger and more mature, eventually reaching the oviduct and being laid out by the queen. Ovary of a laying queen. Individial ovarioles can be seen, with more mature eggs shown as yellowish. Egg cells move down the tube of overioles and become larger and more mature, eventually reaching the oviduct and being laid out by the queen. The spermatheca is shiny, perfectly spherical organ when the tracheal tissues are removed. Important structures in the honey bee reproductive system include the ovary and spermatheca. In the ovary of a laying queen, there are individual ovarioles, with mature eggs appearing yellowish. Egg cells move down the tube of overioles as they become larger and more mature, eventually reaching the oviduct and being laid out by the queen. The spermatheca contains the sperm from the queen’s single mating flight during a one week window around the age of 6-16 days. She will use this sperm to fertilize all the eggs produced in her lifetime. The sperm inside can live up to 4 years. The spermatheca is covered with a rich network of trachea. Once removed, the spermatheca is a shiny, perfectly spherical organ. In un-mated queens, the spermatheca will be clear. Queen breeders learning to use artificial insemination will sometimes check the spermetheca color in a sample of inseminated queens to see if their technique is working. The spermatheca is shiny, perfectly spherical organ when the tracheal tissues are removed. Important structures in the honey bee reproductive system include the ovary and spermatheca. In the ovary of a laying queen, there are individual ovarioles, with mature eggs appearing yellowish. Egg cells move down the tube of overioles as they become larger and more mature, eventually reaching the oviduct and being laid out by the queen. The spermatheca contains the sperm from the queen’s single mating flight during a one week window around the age of 6-16 days. She will use this sperm to fertilize all the eggs produced in her lifetime. The sperm inside can live up to 4 years. The spermatheca is covered with a rich network of trachea. Once removed, the spermatheca is a shiny, perfectly spherical organ. In un-mated queens, the spermatheca will be clear. Queen breeders learning to use artificial insemination will sometimes check the spermetheca color in a sample of inseminated queens to see if their technique is working. |

Very useful photo illustrations – thank you